Herbert Ekwe-Ekwe

SATURDAY 7 October 2017 is the 50th anniversary of the mass execution of 700 Igbo male, boys and men, in Asaba (twin

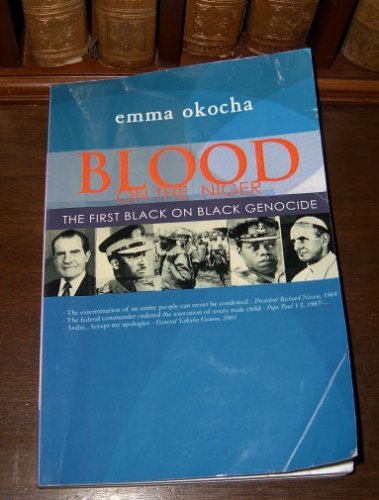

Emma Okocha’s Blood on the Niger (TriAtlantic Books, 2006), a compulsory reference in the study of the Igbo genocide, meticulously catalogues the savagery and aftermath of the Asaba massacre. Okocha, who lost most of his family during the slaughter, survived the execution as a 4-year-old.

(Emma Okocha: onye amuma ndi Igbo)

I cannot tell this story without tears in my eyes … They [genocidist brigade] ordered everyone to come out to the [Asaba] town square … They were honest with us. They told us they were going to kill us. They took us to the mounted machine guns. Then it dawned on us that it was true. I was standing with my older brother at the edge of the crowd. He was holding my hand. He had always taken care of me. We shared the same bed. He was the first to be dragged away by the soldiers. He let go of my hand and pushed me into the crowd. He was shot in the back. I could see the blood gushing from his back. He was the first victim of the massacre. Then all hell let loose. I lost count of time. To this day, I live with the smell of the blood of my brethren that night. Even the heavens wept for the victims of this holocaust. Finally the bullets stopped (Udoka: 2014).

THIS genocide inaugurated Africa’s current age of pestilence.

(John Coltrane Quartet, “Seraphic light” [personnel: Coltrane, tenor saxophone, Alice Coltrane, piano; Jimmy Garrison, bass; Rashied Ali, drums; recorded: Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, US, 15 February 1967])

Twitter @HerbertEkweEkwe

No comments:

Post a Comment