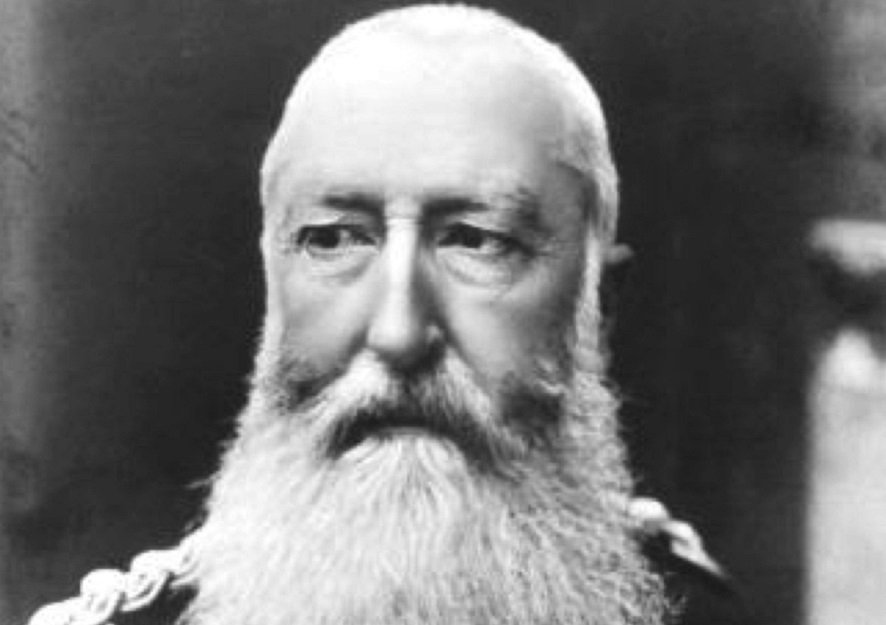

(Leoplold II, genocidist king of the Belgians/state of Belgium, the epitome of this monstrous epithet that calls its “francophonie” Africa, murdered 13 million African peoples in the Congo River basin of central Africa, 1878-1908 – the most expansive

and devastating genocide recorded in Africa, prior to the German

state-organised genocide of Herero people in Namibia, where the Germans murdered 65,000

out of 80,000 Herero or 80 per cent of the total Herero

population wiped out, 1904-1907, and the German state-organised genocide

of Nama people in Namibia, where the Germans murdered 10,000 Nama or 50

per cent of the Nama population wiped out, 1904-1907, the British state/its African-led Nigeria client state organised genocide aganist Igbo people of Biafra, 29 May 1966-present day, in which Britain and its Fulani-overseers in Nigeria and its pan-African constituent nations’ allies of particularly Yoruba, Jukun, Tiv, Urhobo, Edo, Bachama, Jawara, Kanuri, Hausa, Nupe murdered 3.1 million Igbo people, 25 per cent of this nation's population wiped out, during 44 months, 29 May 1966- 12 January 1970, phases I-III, and tens of thousands of additional Igbo murdered by the Anglo-Nigerian African designated genocidists during 13 January 1970-present day, phase-IV) (SEE also update on entry below on former French President Jacques Chirac, made on Friday 11 october 2019)

Herbert Ekwe-Ekwe

SINCE THE 1960s, there has been a persistent populist myth in North World-South World

international politics and relations that the country that retains the

“accolade” as the North World’s most military-interventionist power in the

South is the United States.

Interestingly, this remains the case as a myth! In reality, though, this

unenviable “accolade” in global politics is in fact not held by the United States but France.

And the South’s geographical focus where France appears not to have anything else but

invasion as its own definitive credo

in foreign policy is Africa

(Herbert Ekwe-Ekwe, Readings from

Reading: Essays on African Politics, Genocide, Literature, 2011: 28-34).

In March

2014, The Washington Post ran an editorial on the events in the Crimea

(“President Obama’s foreign policy is based on fantasy”, Washington Post, 2 March 2014, http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/president-obamas-foreign-policy-is-based-on-fantasy/2014/03/02/c7854436-a238-11e3-a5fa-55f0c77bf39c_story.html,

accessed 15 October 2015). Here the paper likens Russia’s policy on this peninsular to

that of a 19th century conqueror-state. Surprisingly, the editorial does not

mention the contemporary world’s lead “19th century-style” invader: France.

In the past five years, France has invaded Côte d’Ivoire, Mali and the Central African Republic and co-led the invasion of Libya. In December 2013, France invaded Central African Republic (CAR). It is its second invasion of the CAR in 12 years. More importantly, this is the 52nd French invasion of the so-called francophonie Africa countries since 1960. In early 2013, it invaded Mali (invasion no. 51); in 2011, it spearheaded the invasion of Libya (no. 50) which also involved Britain and the United States; in 2010, it invaded Côte d’Ivoire, its no. 49 since 1960.

BACK IN 2003, it was

extraordinary to fathom how very hypocritically encased French foreign policy

considerations could be especially when it focused on Africa. Or so it seemed.

For a country that had displayed unrelenting opposition to the then US and

British military intervention in Iraq, France appeared to be basking in the

global populist imagination as, perhaps, the country that not only had invented

the concept of “non-intervention” in other countries’ internal affairs, but was

guided, unambiguously, by this

principle in its own policy in practice. The robust performance of foreign minister Dominique de Villepin during those dramatic January-March 2003 UN security council debates on Iraq would have added vivid credibility to this

assumption (Dominique de Villepin, “Speech by Dominique de Villepin, Minister

of Foreign Affairs, at the United Nations Security Council, New York,

14.02.2003”,In the past five years, France has invaded Côte d’Ivoire, Mali and the Central African Republic and co-led the invasion of Libya. In December 2013, France invaded Central African Republic (CAR). It is its second invasion of the CAR in 12 years. More importantly, this is the 52nd French invasion of the so-called francophonie Africa countries since 1960. In early 2013, it invaded Mali (invasion no. 51); in 2011, it spearheaded the invasion of Libya (no. 50) which also involved Britain and the United States; in 2010, it invaded Côte d’Ivoire, its no. 49 since 1960.

http://www.ambafrance-uk.org/Speech-by-M-Dominique-de-Villepin,4954,

accessed 29 September 2015). In one memorable session in those debates, de

Villepin’s opposition to the impending US-British-led invasion of Iraq drew

unprecedented applause from even usually reticent diplomats. Such were the

liberatory contents in de Villepin’s address that one would not have been too

mistaken if they thought that these had been derived, unedited, from the

seminal papers of Amilcar Cabral (Amilcar Cabral, Return to the Source, 1973;

Cabral, Revolution in Guinea, 1974),

one of the world’s leading restoration-of-independence theorists and

philosophers. De Villepin had in fact stated the following in his 14 February

2003 speech to the security council: “[T]he use of force is

not justified at this time. There

is an alternative to war … Such intervention could have incalculable

consequences for the stability of this scarred and fragile region. It would

compound the sense of injustice, increase tensions and risk paving the way to

other conflicts … This message comes to you today from an old country, France,

from a continent like mine, Europe, that has known wars, occupation and barbarity … Faithful to her values, she believes in

our ability to build together a better world” (added emphasis).

YET A FEW weeks after these eloquent declarations and coupled with the preoccupation of an international media audience intensely focused on the unfolding Iraqi crisis, France invaded Central African Republic (CAR). In the wake of a coup d’état that had toppled the pliant, pro-Paris Angé-Felix Patassé regime in Bangui (CAR capital), France sent its troops into the country, with that invasion being no. 48 in Africa since 1960.

YET A FEW weeks after these eloquent declarations and coupled with the preoccupation of an international media audience intensely focused on the unfolding Iraqi crisis, France invaded Central African Republic (CAR). In the wake of a coup d’état that had toppled the pliant, pro-Paris Angé-Felix Patassé regime in Bangui (CAR capital), France sent its troops into the country, with that invasion being no. 48 in Africa since 1960.

Quintessential

target

“Francophonie” Africa constitutes a

total of 22 countries, mostly in west, northeast, central and southeast Africa

(Indian Ocean) that France conquered and occupied in Africa during the course

of the pan-European invasion of Africa during the 15th-19th centuries. Despite the

presumed restoration of independence, since the 1960s, France, right from the post 1939-1945 war leadership of Charles de Gaulle to the current

François Hollande’s, has such glaring contempt for the notion of

“sovereignty” in these “francophonie” Africa.

Indeed, in practice, the “Brezhnev Doctrine” of the Cold War-era Soviet Union (L S Stavrinos, The Epic of Modern Man, 1971:

465-466; Matthew Ouimet, The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine

in Soviet Foreign Policy, 2003) that had constricted the sovereignty of

the contiguous east European alliance-states, within the strict ambience of the

Warsaw Treaty universe, is a far more progressive relationship than the

typologisation and operationalisation of “francophonie Africa”.

FOR FRANCE, the 22 countries of Africa that are classified as

“francophonie Africa” are France’s personal

property in perpetuity. As a

result, Africa has been the quintessential target of French military interventionism

for 55 years because immanent in the worldview of the French political

establishment, irrespective of ideological/political colouration, none of the

former French-conquered and occupied African states is really seen as independent or sovereign by

any breadth or shade of either of these definitions. Instead, according to this

conception, these are “francophone” backwoods, which, at best, have some

measure of local administrative autonomy (hence, “francophone Africa”!), with

ultimate sovereign power lodged back in Europe – in Paris, as it has been since

the 1885 Berlin conference in which the pan-European World formalised its conquest of Africa (Herbert

Ekwe-Ekwe, “Age of freedom or post-Berlin state Africa”, Pambazuka News, Issue 680, 29 May 2014, http://www.pambazuka.net/en/category/features/91922,

accessed 18 October 2015).

IF EVIDENCE from the highest level of

political authority of the French state is required to buttress this line of

thought, we should recall that very introspectively frank declaration made on

the subject in 1998 by François Mitterand, a former socialist president of

France: “Without Africa, France will have no history in the 21st century” (Tom

Masland, “African Duel”, 1998: 19). This sentiment is underscored by Jacques

Godfrain, former head, French foreign ministry, who frames his own response in

vivid geostrategic terms: “A little country, with a small amount of strength,

we can move a planet because [of our] … relations with 15 or 20 African

countries” (Masland, “African Duel”, 1998: 19). Ten years later, in 2008, another

French president, Jacques Chirac, still indulges in this French obsession to

control Africa in perpetuity when he himself intones: “[W]ithout Africa,

France will slide down into the rank of a third (world) power” (George Bauer,

“Françafrique: Bangui, and the monster”, Graphite

Publications, 9 February 2014, http://graphitepublications.com/francafrique-bangui-and-the-monster/,

accessed 27 August 2015).

(Jacques Godfrain: “A little country, with a small amount of strength, we can move a planet because [of our] … relations with 15 or 20 African countries”)

(Jacques Chirac: “[W]ithout Africa, France will slide down into the rank of a third (world) power”)£££££

It was however France’s post-1939-1945 leader, Charles de Gaulle, who, in 1944, had inaugurated this now

well-known French obsession to control Africa ad infinitum. The irony of the circumstances was indeed not lost on

anyone. Despite France’s early capitulation to Germany in 1940 in the latter’s

war of aggression against its neighbours, de Gaulle, then exiled leader of the

anti-German “French free forces” struggling desperately to effect French

liberation, was himself vociferously opposed to the liberation of Africa.

Africa, we mustn’t forget, was then under the jackboot of French occupation as

well as those of its British and Belgian wartime allies. During the 1944

Brazzaville conference of French overseas-conquest governors which de Gaulle

chaired, he was adamant in what he saw as his vision of the future of

French-occupied Africa: “Self-government must be rejected – even in the more

distant future” (Hubert Deschambs, “France in Black Africa and Madagascar

between 1920 and 1945”, in LH Gann and Peter Duiganan, eds., Colonialism in Africa, 1870-1900. Vol. Two:

The History and Politics of Colonialism 1914-1960, 1970: 249).

(Charles de Gaulle: “Self-government [restoration of African independence] must be rejected – even in the more distant future”)

Supercilious antagonism

De Gaulle’s supercilious antagonism

to African liberation was of course not unique at the time. Similar sentiments

were evident in the position of Winston Churchill, the British prime minister,

who insisted in 1942 that he had not attained his position as head of

government to “preside over the liquidation of the British empire” (“From our archive: Mr Churchill on our one aim”, The Guardian [London], 11 November 2009, http://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2009/nov/11/churchill-blood-sweat-tears,

accessed 24 September 2015). The Belgian king and government, who barely

resisted Germany’s attack and overrun of their country beyond three weeks in

May 1940, were themselves equally unwilling to discontinue their occupation of

the Congo (Democratic Republic of the Congo) after Germany’s eventual defeat in

1945. This was in spite of the central role that the Congo played in the

financing of the Belgian war effort (including the entire expenses of the

country’s exiled royal family and government in London) which totalled the

grand sum of £40 million. “In fact, thanks to the resources of the Congo, the

Belgian government [in exile] in London had not to borrow a shilling or a

dollar, and the Belgian gold reserve could be left intact”, recalls Robert

Godding, the then Belgian government-in-exile secretary with direct

responsibility for the occupation of the Congo (Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, 1972:

188). Besides, Belgium had, earlier on

in Africa, carried out a catastrophic 30-year trail (1878-1908) of genocide

against Africans in the Congo basin in which it annihilated 13 million

constituent peoples (Isidore Ndaywel è Nziem, Histoire

générale du Congo: De l'héritage ancien à la République Démocratique, 1998: 344). Leopold II, the génocidaire king who

supervised this carnage was equally obsessed with Belgian’s own share of the conquest and occupation

of Africa: “I do not want to risk … losing a fine chance to

secure for ourselves a slice of this magnificent African cake” (Adam

Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost, 1999:

58).

(Leopold II: “I do not want to risk … losing a fine chance to secure for ourselves a slice of this magnificent African cake”)

BUT UNLIKE British and Belgian

leaders (the latter were ultimately welded into the encompassing French-led francophoniedom), de Gaulle pursued

France’s long time ambitions in Africa with almost megalomaniac intensity in

the years after 1945 – opposing African liberation projects in the west and

central regions of the continent, under French occupation, as well as on the

islands off the east coast in the Indian Ocean especially Madagascar. However

in 1958, de Gaulle changed track, somewhat, in his anti-African independence

drive. Stung and disillusioned by the 1954 spectacular and humiliating defeat

of French forces in Vietnam and the looming disaster in its ongoing war in

Algeria, de Gaulle produced a document for a purported future of African

freedom. In the main, this document envisioned a circumscribed African independence outcome that would ensure

continuing French political and economic hegemony in Africa (Jean Allman,

“Between the present and history: African nationalism and decolonization”, Oxford Handbooks Online, December 2013, http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199572472.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199572472-e-005,

accessed 16 August 2015). Apart from Guinea, which opposed it when it was put

to a referendum, France succeeded in imposing the document on the rest of its

occupied states, with evident compliance with some segments of the African

leaderships of the restoration-of-independence movement and the all too

familiar tragic consequences since.

Operationalisation…

The stage was now set for France to

invoke the licence, at its own choosing, to intervene in the political process

of any of its prized African lands of “francophonie”: invade, intimidate,

manipulate, install, antagonise, ingratiate, indemnify, expropriate, invade,

intimidate... Hardly any of the 22 African countries in “francophonie” escaped

this epoch of witnessing the invasion of their territory by some contingent of

the French military from one of its numerous bases in the region or from those

further away back home in Corsica. Each of these African “francophonie” states

“hosts” a French military base of varying capabilities and configuration as

part of this overarching network in which Dakar, Sénégal, is at its epicentre,

in turn linked to requisite interventionist brigades positioned in Corsica.

Thanks to this network, the French military has invaded this African

“francophonie” enclave 52 times, since

1960, as we have stated – from Chad to the Congo (Congo Democratic

Republic), Côte d’Ivoire to the Comoros. Such invasions provide the French the

opportunity to directly manipulate local political trends in line with their

strategic objectives, install new client regimes, if need be, and expand the

parameters of expropriation of critical resources even further as unabashedly vocalised

by many a president.

ON THIS SCORE, the so-called Congo Democratic Republic

(or Zaïre or Congo-Kinshasa as it has been variously called), the jewel in the crown of “francophonie”, is

aptly illustrative. Between 1961 and 1996, France intervened militarily in the

country 17 times to prop up the notorious dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko

which ravaged one of Africa’s richest economies. Countries such as Central

African Republic (or Central African Empire as it was known when it was ruled,

literally, by the very francophile acolyte and dictator, Jean-Bédel Bokassa),

Rwanda (French military intervention was ongoing in the country as the forces

of the pro-French central government perpetrated its dreadful genocide against

the Tutsi in 1994), Burundi, Djibouti and Chad bore the brunt of the invasions

as France sought to enforce or safeguard the fortunes of one client regime or

the other. For France, therefore, its hegemonic control of “francophone Africa”

in the past 55 years has been a lucrative and “prestigious” rearguard quest to

maintain a stranglehold of influence in the Southern World, despite the obvious

militarily weakened position of its overall international status after the end

of the Second World War – or as from indeed 27 years earlier, following the end

of the 1914-1918 war (Ekwe-Ekwe, Readings

from Reading: 57-58). Former head of French foreign ministry Jacques

Godfrain’s geostrategic observation, quoted earlier, couldn’t have been more correctly

stated: “A little country, with a small amount of strength, we can move a

planet because [of our] ... relations ... with 15 or 20 African countries”.

SO, keeping a stranglehold on “francophonie

Africa” enables France, with an

astonishingly fragile, struggling economy, to scoop gargantuan levels of

capital, mineralogical and agricultural resources that it couldn’t

ever generate in its own homeland, year in, year out. Furthermore, so brutally a double-jeopardy,

Africans, themselves, pay

for France’s military invasions of “francophonie Africa” as Gary Busch, a

political economist, shows in his 2011 excellent research on the subject with

the stunning title, “Africans pay for the bullets the French use to kill them”.

Busch draws the world’s attention to the key “settlement documents” mapped out

by France, back in 1960, that

marks its envisaged future relations with “francophonie Africa” (Gary Busch,

“Africans pay for the bullets the French use to kill them”, nigeriavillagesquare, 29 July 2011, http://nigeriavillagesquare.com/forum/articles-comments/64584-africans-pay-bullets-french-use-kill-them.html, accessed 15 August 2015):

France is holding billions of dollars owned by African [“francophonie”] states in its own accounts and invested in the French bourse … [“Francophonie”] African states deposit the equivalent of 85% of their annual reserves in [dedicated Paris] accounts as a matter of post-[conquest] agreements and have never been given an accounting on how much the French are holding on their behalf, in what these funds been invested, and what profit or loss there have been.

(Paris Bourse)

IT IS PRECISELY because of this

French blanket control of the critical finances of “francophonie Africa” that

no French president, during this epoch of consideration (from de Gaulle to

Hollande), has found it necessary to go to the national assembly and seek

authorisation for any of the 52 invasions of Africa in 55 years not to mention

seek a franc or euro from the legislature to fund the escapade! In effect, France appropriates crucial African financial

resources generated in Africa but transferred to and reserved and

controlled in Paris to invade Africa and secure even more African

resources… As a result of this continuing inordinate leverage exercised by

France in Africa, in addition to that of Britain’s, these two foremost

pan-European World conqueror-states of Africa currently have a greater secured access to Africa’s critical resources than at

any time during decades of their formal occupation of the continent (Herbert

Ekwe-Ekwe, “Rethinking the state in Africa …

Whose state is it? Paper read at Conference on ‘Rawls in Africa’ in honour of Professor Ifeanyi Menkiti, Wellesley College”, 10 May 2014, http://re-thinkingafrica.blogspot.co.uk/2014/05/rethinking-state-in-africa-whose-state.html, accessed 18 October 2015).

Origins

BUT WHY THESE these 22 countries in Africa – at least 3000 miles away from France? Why Africa? Why not Asia, perhaps, or the Arab World, a people closer home to France? But aren’t these 22 African countries sovereign or rather “francophonie”, as France insists? Are these categorisations, “sovereign” and “francophonie” synonymous? If so, how? If not, why not? Yet the crucial question remains: Why Africa?

BUT WHY THESE these 22 countries in Africa – at least 3000 miles away from France? Why Africa? Why not Asia, perhaps, or the Arab World, a people closer home to France? But aren’t these 22 African countries sovereign or rather “francophonie”, as France insists? Are these categorisations, “sovereign” and “francophonie” synonymous? If so, how? If not, why not? Yet the crucial question remains: Why Africa?

France has long been wracked by chronic

anxieties about its “status” and “prestige” in the world since its military was

dealt a humiliating defeat during the 12-year old uprising (1792-1804) by enslaved

African military forces led by Toussaint L’Ouverture in French-occupied San

Domingo (Haiti) in the Caribbean – the “greatest individual market” of the 18th

century European enslavement of the African humanity, which accounted for

two-thirds of French foreign trade at the time (CLR James, The Black Jacobins, 2001: xviii). The Africans of San Domingo, “The

Black Jacobins”, as CLR James, the illustrious African Caribbean scholar would

describe them in such searing irony if not sardonicism in his 1938-published

classic of the same title on the subject, “defeated in turn the local whites

and the soldiers of the French monarchy, a Spanish invasion, a British

expedition of some 60,000 men, and a French expedition of similar size under

[Napoleon] Bonaparte’s brother-in-law” (James: xviii). Following the latter’s

victory in 1803, the Africans proclaimed and established their republic of

Haiti on 1 January 1804.

(Toussaint L’Ouverture)

FRANCE HAS YET to recover from the catastrophic

damage to its psyche, elicited by its losses in San Domingo, effectuated by the

transformation of enslaved Africans,

as James notes perceptively in his study, “trembling in hundreds before a

single white man … into a people able to organise themselves and defeat the

most powerful European nations of their day … [This] is one of the great epics

of revolutionary struggle and achievement” (James: xviii). Consequently, in its

relationship with Africans, wherever this occurs on earth, France feels that it

is still fighting Toussaint L’Ouverture and his formidable forces all over

again and again… Furthermore, San Domingo is gravely etched indelibly in French

consciousness as the precursor to the catalogue of crushing French military

defeats in the subsequent 150 years of its history, aptly illustrated by the

following: the 1871 Franco-Prussian War, the 1914-1918 war, the

1939-1945 war and the 1954 Battle of Dien Bien Phu resulting in the débâcle

of its elite French Far East Expeditionary Corps’s occupation garrison in

Vietnam, inflicted by the resolute Viet Minh commanded by General Giáp (Peter

MacDonald, Giap: The Victor of Vietnam,

1993).

It would require another site of examination to

discuss, more fully, how this indelible French angst over San Domingo must have

worked through the mindset of Nicholas Sarkozy, a latter day occupant of the

Élysée palace, whose regime thrived in its serial fantasy as the neo-Napoleonic

imperium of these early decades of the 21st century. Evidently convulsed by the

legacy of San Domingo, Sarkozy, in July 2007, engaged in a thuggish foul-mouthed

theatrics of a so-called address “on Africa” to an African audience in Dakar, Sénégal,

that should have sought auditioning elsewhere rather than the stage of the

hallowed auditorium of the Cheikh Anta Diop University, named after the great

African polymath (“The unofficial English translation of Sarkozy’s speech”, africaResource, 13 October 2007,

http://www.africaresource.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&catid=36:essays-a-discussions&id=437:the-unofficial-english-translation-of-sarkozys-speech,

accessed 19 August 2015). Undoubtedly, Sarkozy knew, fully well, that his

audience was made up of none other than the proud heirs and heiresses of those actualisers of

history on the estates of San Domingo just 210 years earlier.

Handwriting on the wall

In essence, the audience in that

July 2007 Dakar auditorium detected that Sarkozy, head of the French state of

the day, was already reading the unmistakable handwriting on the wall about the

prospects of “francophonie” in Africa. Despite its near-monolithic activity in

the lives of generations and the resultant semblance of durability, the

importance and influence of “francophonie” in Africa is beginning to wane.

Events in Africa in the past 21 years have seriously weakened and undermined

its efficacy. The Tutsi genocide in Rwanda, organised premeditatedly by

France’s ruthless local clients in power in Kigali whilst a French

expeditionary force was operating in the country, was a monumental indictment

of the entire “francophonie” project in Africa, reinforcing the gory

legacy of the earlier, Belgian-francophonie genocide in the Congo basin which destroyed

the lives of 13 million Africans. France could not escape complicity in the

murder of 800,000 Africans in Rwanda in 1994. Pointedly, there has been a

partial eclipse of French influence in this central/southern Africa region

since the latter genocide.

THE POPULAR overthrow and subsequent death in exile of Congolese dictator Mobutu, during the same period, was a further blow to the fortunes of “francophonie” in the region. Elsewhere in the empire, the tentacles of “francophonie” were also beginning to unravel. The situation in the Côte d'Ivoire economic powerhouse was of particular relevance. The sudden death in 1993 of Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the Ivorian political colossus who had been state president since 1960, created a serious crisis of succession in the country that still remains unresolved. In 2002, it became the background of a tragic war between the state and insurgents in its north region and the precipitate collapse of Africa’s most successful economy that followed a decade later by the French invasion of the country and its installation of a client regime in Abidjan. But in Sénégal, France’s attempt to continue to dictate its choice of leaders in this northwest stretch of “francophonie” was rejected massively in the 2000 presidential elections when Abdoulaye Wade, the veteran opposition politician, defeated Abdou Diouf, the incumbent president and Paris’s much preferred candidate, and in the choice of president, 12 years later, in the post-Wade era.

In a desperate effort to stem the steady decline of “francophonie”, France embarked on its biennial so-called African-French summit that extends invitation to leaders of non-league states. It was in this context of “francophonie”-extension in the 1990s that France intensely courted the friendship of Sani Abacha, the Nigerian dictator and génocidaire military commander who participated in the 1966-1970 Igbo genocide, who was at the time internationally quarantined as a result of his regime’s continuing deteriorating human rights records. Abacha’s predictable appreciation at this gesture of breaking out of painful political and economic isolation was followed by a deft regime decision that keyed into the inner workings of the infrastructure of “francophonie”: Nigeria would hence embark on an intensive educational/allied cultural programme to “adopt” French as an “additional” lingua franca to English! Paris was of course delighted! But it was very short-lived indeed. The lingua franca opportunism died with the génocidaire and dictator in 1998!

THE POPULAR overthrow and subsequent death in exile of Congolese dictator Mobutu, during the same period, was a further blow to the fortunes of “francophonie” in the region. Elsewhere in the empire, the tentacles of “francophonie” were also beginning to unravel. The situation in the Côte d'Ivoire economic powerhouse was of particular relevance. The sudden death in 1993 of Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the Ivorian political colossus who had been state president since 1960, created a serious crisis of succession in the country that still remains unresolved. In 2002, it became the background of a tragic war between the state and insurgents in its north region and the precipitate collapse of Africa’s most successful economy that followed a decade later by the French invasion of the country and its installation of a client regime in Abidjan. But in Sénégal, France’s attempt to continue to dictate its choice of leaders in this northwest stretch of “francophonie” was rejected massively in the 2000 presidential elections when Abdoulaye Wade, the veteran opposition politician, defeated Abdou Diouf, the incumbent president and Paris’s much preferred candidate, and in the choice of president, 12 years later, in the post-Wade era.

In a desperate effort to stem the steady decline of “francophonie”, France embarked on its biennial so-called African-French summit that extends invitation to leaders of non-league states. It was in this context of “francophonie”-extension in the 1990s that France intensely courted the friendship of Sani Abacha, the Nigerian dictator and génocidaire military commander who participated in the 1966-1970 Igbo genocide, who was at the time internationally quarantined as a result of his regime’s continuing deteriorating human rights records. Abacha’s predictable appreciation at this gesture of breaking out of painful political and economic isolation was followed by a deft regime decision that keyed into the inner workings of the infrastructure of “francophonie”: Nigeria would hence embark on an intensive educational/allied cultural programme to “adopt” French as an “additional” lingua franca to English! Paris was of course delighted! But it was very short-lived indeed. The lingua franca opportunism died with the génocidaire and dictator in 1998!

Tenuous

IT IS NOW clear that the tenuousness

of “francophonie Africa” lies right in its foundational premise of operationalisation:

the incorporation of a league of countries that exists solely to serve French interests whilst critically dependent on its

day to day overseeing on usually ruthless anti-African local regimes. This

ruthlessness is a feature of its overarching moral and intellectual bankruptcy

which ensures that it does the bidding of such projects as “francophonie” or “francophonie-extension”

because of the firm grip that it exercises within a designated “home turf”.

This is why the head of this “home turf” is bereft of any disposition of

responsibility to “home”, howsoever this is defined, but is existentially

sutured to the palace of Élysée’s priorities and

diktat.

Paradoxically, though, this French grip

on these regions of Africa is all too brittle as can be seen in the immediate

consequences on “francophonie” in the event of the overthrow or death of the

dictator. The leaderships of the French state find it extremely difficult to

contemplate that, with the steadily growing and expansive African grassroots’

pressure on their inept African-led regimes which can only intensify, “francophonie” has

no long-term prospects in Africa. While the overall socio-economic situation

across the continent is currently in a state of flux, Africa is unlikely to

return to that spurious stability epoch of the Houphouët-Boignys and Senghors

or the murderous repression of the Mobutus and Bokassas which enhanced the

development of “francophonie”. Inevitably, if

“francophonie Africa” is France’s comprehensive subjugation of the African

humanity, as French leaderships since the 1960s, from de Gaulle to Hollande, have

hardly had any cause to disguise, the dual prime questions of the age must be:

When will the Africans involved in this staggering 21st century outrageous subjugation

bring it to an end? Isn’t it now obvious that “francophonie Africa” – CAR,

Mali, Niger, Congo Democratic Republic, Congo Republic, Burundi, Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, whatever, wherever, cannot

hold?

FRANCE WILL realise much sooner than

later that it cannot continue to enrich itself from Africa and consequently construct

some phantom prestige in international relations based on its control of the

destiny of Africa and Africans.

---------------------------------------------

£££££: ACCORDING TO THE RECENTLY released major indictment made by Richard Dearlove, former head of the mi6 British military intelligence, there wasn’t anything “principled” or “honourable” in Jacques Chirac’s opposition to the US-British invasion of Iraq as Saddam Hussein, the Iraqi head of regime, “bribed” Chirac with the sum of £5 million, paid through “intermediaries” into Chirac’s personal bank accounts during the period, to enable him take that position (see Abul Taher and Peter Henn, “Saddam Hussein ‘bribed Jacques Chirac’ with £5million in bid to make the former French president oppose the US-led Iraq war”, Mail on Sunday, London, 29 September 2019, accessed 29 September 2019)

---------------------------------------------

£££££: ACCORDING TO THE RECENTLY released major indictment made by Richard Dearlove, former head of the mi6 British military intelligence, there wasn’t anything “principled” or “honourable” in Jacques Chirac’s opposition to the US-British invasion of Iraq as Saddam Hussein, the Iraqi head of regime, “bribed” Chirac with the sum of £5 million, paid through “intermediaries” into Chirac’s personal bank accounts during the period, to enable him take that position (see Abul Taher and Peter Henn, “Saddam Hussein ‘bribed Jacques Chirac’ with £5million in bid to make the former French president oppose the US-led Iraq war”, Mail on Sunday, London, 29 September 2019, accessed 29 September 2019)

(Wayne Shorter Octet, “Mephistopheles” {composer Alan Shorter} [personnel: Wayne horter, tenor saxophone; Freddie Hubbard, trumpet; Alan Shorter, fluegelhorn; Grachan Moncur III, trombone; James Spaulding, alto saxophone; Herbie Hancock, piano; Ron Carter, bass; Joe Chambers, drums; recorded: Van Gelder Studio, Englewood, NJ, US, 15 October 1965])Works cited

Africa

Resource. “The unofficial English translation of Sarkozy’s speech”. 13 October

2007,

http://www.africaresource.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&catid=36:essays-a-discussions&id=437:the-unofficial-english-translation-of-sarkozys-speech,

accessed 19 August 2015.

Afrohistorama. 20 August 2011, http://www.afrohistorama.info/article-africans-pay-for-the-bullets-the-french-use-to-kill-them-82337836.html, accessed 15 August 2015.

Afrohistorama. 20 August 2011, http://www.afrohistorama.info/article-africans-pay-for-the-bullets-the-french-use-to-kill-them-82337836.html, accessed 15 August 2015.

Allman, Jean. “Between the present

and history: African nationalism and decolonization”. Oxford Handbooks Online, December 2013, http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199572472.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199572472-e-005,

accessed 16 August 2015.

Bauer, George. “Françafrique:

Bangui, and the monster”. Graphite

Publications, 9 February 2014, http://graphitepublications.com/francafrique-bangui-and-the-monster/,

accessed 27 August 2015.

Busch, Gary. “Africans pay for the

bullets the French use to kill them”. Nigeriavillagesquare, 29 July 2011, http://nigeriavillagesquare.com/forum/articles-comments/64584-africans-pay-bullets-french-use-kill-them.html, accessed 15 August 2015.

Cabral, Amilcar. Return to the Source: Selected Speeches of

Amilcar Cabral. New York: Monthly Review, 1973.

Cabral, Amilcar. Revolution in Guinea: An African People’s

Struggle. Selected Texts. New York: Monthly Review, 1974.

http://www.ambafrance-uk.org/Speech-by-M-Dominique-de-Villepin,4954,

accessed 29 September 2015.

Deschambs, Hubert. “France in Black Africa and Madagascar

between 1920 and 1945”. In L.H. Gann and Peter Duiganan, eds., Colonialism in Africa, 1870-1900. Vol. Two:

The History and Politics of Colonialism 1914-1960. Cambridge: Cambridge

University, 1970.

Ekwe-Ekwe, Herbert. “Age of freedom

or post-Berlin state Africa”, Pambazuka

News, Issue 680, 29 May 2014, http://www.pambazuka.net/en/category/features/91922,

accessed 18 October 2015.

Ekwe-Ekwe, Herbert. “Rethinking

the state in Africa … Whose state is it?”. Paper read at “Conference on ‘Rawls

in Africa’ in honour of Professor Ifeanyi Menkiti”. Wellesley College, 10 May

2014, http://re-thinkingafrica.blogspot.co.uk/2014/05/rethinking-state-in-africa-whose-state.html, accessed 18 October 2015.

Ekwe-Ekwe, Herbert. Readings from

Reading: Essays on African Politics, Genocide, Literature. Reading and Dakar:

African Renaissance, 2011.

Guardian, The. “From our archive: Mr Churchill on our one

aim”. The Guardian, London, 11

November 2009, http://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2009/nov/11/churchill-blood-sweat-tears,

accessed 24 September 2015.

Hochschild, Adam. King Leopold’s Ghost. Boston: Houghton

Mifflin Harcourt, 1999.

Isidore Ndaywel è Nziem. Histoire générale du Congo: De l'héritage ancien à la République Démocratique. Paris: Duculot, 1998.

James, CLR. The Black Jacobins. London: Penguin, 2001.

“King Leopold’s Ghost”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King,

accessed 20 August 2014.

MacDonald, Peter. Giap: The Victor of Vietnam. New York:

WW Norton Publishers, 1993.

Masland, Tom. “African Duel”. Newsweek, Washington, 30 March 1998.

Ouimet, Matthew. The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy. Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina, 2003.

Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. London: Bogle L’Ouverture, 1972.

Stavrinos, L. S. The Epic of Man. Englewood Cliffs:

PrenticeHall, 1971.

Washington Post. “President Obama’s

foreign policy is based on fantasy”. Washington, 2 March 2014,

http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/president-obamas-foreign-policy-is-based-on-fantasy/2014/03/02/c7854436-a238-11e3-a5fa-55f0c77bf39c_story.html,

accessed 15 October 2015.

Wayne Shorter Octet. “Mephistopheles”. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, US: Van Gelder Studio, 15 October 1965.

******Herbert Ekwe-Ekwe’s books on the Igbo genocide and Biafra include Readings from Reading, Essays on African Politics, Genocide, Literature (2011), Biafra Revisited (2006) and African Literature in Defence of History: an essay on Chinua Achebe (2001)

******Herbert Ekwe-Ekwe’s books on the Igbo genocide and Biafra include Readings from Reading, Essays on African Politics, Genocide, Literature (2011), Biafra Revisited (2006) and African Literature in Defence of History: an essay on Chinua Achebe (2001)

Twitter @HerbertEkweEkwe

No comments:

Post a Comment